Dear Reader,

I know this blog is a bit later than the first Friday, but I was asked to write a guest post for HoCoPoLitSo (Howard County Poetry and Literature Society) to mark LGBTQ History Month, and I wanted to let that post get published first there before I published a slightly different version of it here – so much has happened since I submitted the blog to them, and I kept thinking/writing. Now that it’s up there, here it is. You can also check it out on HoCoPoLitSo’s blog.

————————————————————–

October is LGBTQ History Month. When I think about LGBTQ history, I am of two minds and the poems included in the LGBTQ collection on Poets.org perfectly reflect that split. Some of the poems are so absolutely ordinary in their subjects, like the poem, “our happiness” by Eileen Miles, and on one hand, I think, that’s progress: the lives of LGBTQ people are written and expressed in the same way as other lives. That’s equality, right? Being a gay poet doesn’t mean that you have to write every poem about the experience of being gay. Not every aspect, every moment of my life is about that, but my experience is most definitely shaped by it and so is my view of history.

If we’re really talking about history, the conversation is incomplete unless we acknowledge that nothing is really the same. Some might say, hey, you won the right to get married, so what are you complaining about? That reminds me of the poem, “On Marriage” by Marilyn Hacker where the poet talks about the way in which LGBTQ people “must choose, and choose, and choose / momently, daily” to affirm their  commitment to one another, “Call it anything we want” when society doesn’t quite know how to accept or handle this kind of “covenant.” We talk a lot about “White Privilege” in cultural discourse, but we don’t talk a lot about “Mainstream Heterosexual Cisgender Privilege.” It exists. MHCP allows folks to do very ordinary things like hold hands in public without having to do a quick check of their surroundings. MHCP allows you to use whatever bathroom you want without being harassed or shamed or threatened. It allows you to feel “normal” out in the world. Put it this way: there are times when showing affection to my wife in public – just a peck on the cheek – feels like a dangerous political act.

commitment to one another, “Call it anything we want” when society doesn’t quite know how to accept or handle this kind of “covenant.” We talk a lot about “White Privilege” in cultural discourse, but we don’t talk a lot about “Mainstream Heterosexual Cisgender Privilege.” It exists. MHCP allows folks to do very ordinary things like hold hands in public without having to do a quick check of their surroundings. MHCP allows you to use whatever bathroom you want without being harassed or shamed or threatened. It allows you to feel “normal” out in the world. Put it this way: there are times when showing affection to my wife in public – just a peck on the cheek – feels like a dangerous political act.

It hasn’t always been this way for me. In fact, I enjoyed MHCP for most of my life. I went to a conservative Christian high school, and though there were probably gay people around me (I’m pretty sure a few of my teachers were/are), since none of them were out, I feel as though I didn’t meet a gay person until I went to college. Riding through my high school years and my twenties as an MHCP was easy. Being white made it even easier. Realizing I was gay later in life when I care less what the world thinks has made the sting of discrimination sting a little less. Still, it was surprising to realize that the world had changed. Is it weird to say that I want to have it both ways? As Uncle Walt says, “Very well then I contradict myself, / I am large, I contain multitudes.” I want everyone in the world to see LGBTQ people as just normal, and I want everyone to know that our experience is different.

If we’re talking about history, we have to acknowledge that being an LGBTQ person  is a unique and still unequal experience in this country. There are subtle and unsubtle ways that society is set up to exclude and marginalize us. And some of the poems I browsed on Poets.org do address that fact. I find myself drawn more powerfully to these poems because I do want to acknowledge the difference that exits. A great example of this is “A Woman Is Talking to Death” by Judy Grahn. The poem was written in 1940, and the lines that jump out to me are:

is a unique and still unequal experience in this country. There are subtle and unsubtle ways that society is set up to exclude and marginalize us. And some of the poems I browsed on Poets.org do address that fact. I find myself drawn more powerfully to these poems because I do want to acknowledge the difference that exits. A great example of this is “A Woman Is Talking to Death” by Judy Grahn. The poem was written in 1940, and the lines that jump out to me are:

“this woman is a lesbian, be careful.

When I was arrested and being thrown out

of the military, the order went out: don’t anybody

speak to this woman, and for those three

long months, almost nobody did: the dayroom, when

I entered it, fell silent til I had gone; they

were afraid, they knew the wind would blow

them over the rail, the cops would come,

the water would run into their lungs.

Everything I touched

was spoiled. They were my lovers, those

women, but nobody had taught us how to swim.

I drowned, I took 3 or 4 others down

when I signed the confession of what we

had done together.

No one will ever speak to me again.”

LGBTQ history is a history of fraught silence. A friend of mine, Rob, hid the fact that he was gay the entire time he was in the Navy – it wasn’t just that he feared for his job, he also feared for his life, that other soldiers might threaten or harass him for being openly gay. He hid it until he completed his tour of duty, and then he came out to all of his friends. You might think that passing a law abolishing “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” would end this discrimination, but you would be wrong. This discrimination still exists in the military – though now the target has shifted from being gay or lesbian to being transgender. Grahn’s poem was written in 1940; it is 77 years later, and we are not there yet. And because we live in the age of vindictive executive orders, we are too afraid that the next step in the movement will be a step backward.

If we’re talking about history, we have to acknowledge that we’re still in the middle of the story right now. What started with Alan Turing, Barbara Gittings, Christine Jorgenson, Alan Ginsberg, Walt Whitman, the Stonewall riots, James Baldwin, and Harvey Milk has led us to the defeat of DOMA, the rejection of Proposition 8, the victory of Edith Windsor, the success of Tammy Baldwin. But this complicated history also continues with events like the shooting in the Pulse nightclub and pronouncements that threaten the rights of transgender soldiers and that reinterpret Civil Rights laws to exclude protections for

One of the happiest days in my life was November 6th, 2012. That was the day that voters in my home state of Maryland affirmed the right of gay and lesbian couples to marry, and I knew that I would marry my wife. Then, on June 26th, 2015, the United States Supreme Court ruled that we should be seen as equal under the law. In a stunning closing paragraph, Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote, “Their hope is not to be condemned to live in loneliness, excluded from one of civilization’s oldest institutions. They ask for equal dignity in the eyes of the law. The Constitution grants them that right.” To read

© Ryna May 2017

politician – he just says what he thinks when he thinks it – no filter. In

politician – he just says what he thinks when he thinks it – no filter. In

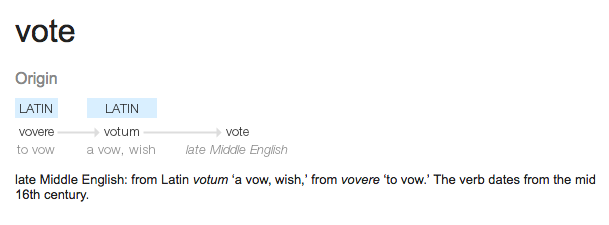

I am not going to say that you should vote for one candidate over the other. You are not wrong to note that I seriously question the virtue of voting for Donald Trump, but by default, that does not mean that I think you should vote for Hillary Clinton. I think you should critically think about it. There are actually 4 parties and 4 candidates to choose from this election year (

I am not going to say that you should vote for one candidate over the other. You are not wrong to note that I seriously question the virtue of voting for Donald Trump, but by default, that does not mean that I think you should vote for Hillary Clinton. I think you should critically think about it. There are actually 4 parties and 4 candidates to choose from this election year (

at night when I was sad or scared and could not sleep and go huddle right in front of my mom’s living room stereo. The first night I did it, I just pushed play on the tape deck and the sound came out at me like a warm blanket, wrapped me up, and hushed me to sleep. After that first night, whenever I found myself too traumatized to sleep, I crawled to the stereo in search of that peaceful lullaby. Play. Rewind. Play. Rewind. Until sleep came over me. Years later, when I was in high school, I had a friend who was learning to play it, and I could not get enough of listening to her play those first few measures. Even today the song elicits a physical reaction – a deep breath and warm tingle that runs up the spine.

at night when I was sad or scared and could not sleep and go huddle right in front of my mom’s living room stereo. The first night I did it, I just pushed play on the tape deck and the sound came out at me like a warm blanket, wrapped me up, and hushed me to sleep. After that first night, whenever I found myself too traumatized to sleep, I crawled to the stereo in search of that peaceful lullaby. Play. Rewind. Play. Rewind. Until sleep came over me. Years later, when I was in high school, I had a friend who was learning to play it, and I could not get enough of listening to her play those first few measures. Even today the song elicits a physical reaction – a deep breath and warm tingle that runs up the spine.